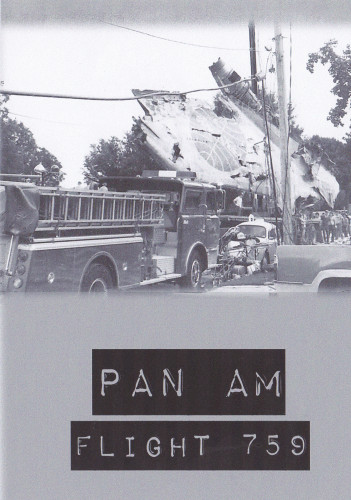

A shot of neighborhood damage from Pan Am Flight 759’s crash in Kenner. Photo credit: Baye, John (Photographer) & Anderson, Summer (Graphic Designer)

Exactly 32 years and one day ago, a Pan American World Airlines plane that departed from New Orleans crashed in a suburban neighborhood in Kenner, making it the fifth deadliest crash in US aviation history to date. Our partner site, KnowLA, The Digital Encyclopedia of Louisiana History and Culture, looks at the Pan Am Flight 759 crash of July 9, 1982.

On the afternoon of July 9, 1982, shortly after Pan American World Airlines (Pan Am) Flight 759 lifted off the runway with 146 passengers and crew en route from New Orleans to Las Vegas, Nevada, the Boeing 727 crashed into a suburban neighborhood in Kenner, Louisiana, killing all on board and eight on the ground. At the time, the crash was the second deadliest in US aviation history; as of 2013, it remains the fifth deadliest. Investigators with the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that a microburst-induced wind shear was the cause, and the disaster led to the development of sophisticated equipment that incorporates Doppler radar to predict severe downdrafts, virtually eliminating the violent weather phenomenon as a threat to airline safety. Wind-shear detection and alert systems were mandated by the US Federal Aviation System for installation in all commercial aircraft by 1993.

Originating in Miami, Florida, Flight 759 made its first stop in New Orleans. Las Vegas was scheduled as the third destination, followed by San Diego, California. The plane was cleared for takeoff under heavy thunderstorms at 4:09 PM by the control tower at New Orleans International Airport (now named Louis Armstrong International Airport). The aircraft was suddenly forced down into the Roosevelt subdivision four minutes after it was airborne over Kenner, at no more than 100 feet in altitude, by a microburst, a tight column of sinking air that produces intense straight-line winds at ground level that are similar to but distinguishable from a tornado.

Captain Kenneth L. McCullers and copilot Donald G. Pierce, knowing that a crash landing was imminent, veered the plane to the left toward the nearby West Metairie Canal in a desperate attempt to redirect the plane away from a residential neighborhood. In the process, the plane clipped trees and snapped a power line. The left wing plowed into the ground, causing the plane to cartwheel, skid, and explode with more than eight thousand gallons of unspent jet-fuel aboard. Flight 759 cut a deadly swath through Kenner, destroying six homes and damaging five others in a four-block area less than 5,000 feet from the end of the runway.

Though the damage was catastrophic, McCullers and Pierce’s last-minute decision saved many lives. If not for their courageous act in the face of death, the surrounding Morningside Park neighborhood could have been completely wiped out. McCullers was a veteran of several emergencies, including a dramatic in-flight loss of all electrical power on New Year’s Day 1979; he was commended for bringing that passenger jet to a safe landing in Houston, Texas.

Dr. Robert Barsley — who had graduated from the Louisiana State University School of Dentistry in 1977 but had gone on to become president of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences — was assigned to help identify people from twenty-three different countries killed in Pan Am Flight 759; it was his first week working as a forensic dentist.

In the midst of searching the scorched debris for body parts or potential survivors, Jefferson Parish Deputy Gerald Hibbs discovered eighteen-month-old Melissa Trahan, who became known as the “Miracle Baby.” Hibbs thought he saw something move on the ground then thought he heard a noise. He flipped over a mattress and rescued Trahan, who had likely survived when the mattress and other debris shielded her body from the jet-fuel inferno. Trahan’s mother and four-year-old sister were among the fatalities.

A report issued by the NTSB on March 25, 1983, declared that “low-level wind shear conditions had been detected by the airport’s [alert system] and the system had alarmed several times, the last time about four minutes before Flight 759’s takeoff. The system was not alarming at the time the takeoff clearance was issued; however, a wind shear advisory was broadcast two seconds after the accident.” The NTSB recommended that “advisories be amended promptly to provide current wind-shear information and other information pertinent to hazardous meteorological conditions in the terminal area as provided by Center Weather Service Unit meteorologists, and that all aircraft operating in the terminal area be advised by blind broadcast when a new Automatic Terminal Information Service advisory has been issued.”

Radar systems were upgraded nationwide in the aftermath, and New Orleans International Airport reevaluated runways that ran perilously close to densely inhabited areas of suburban Jefferson Parish. A revenue-sharing plan was worked out with neighboring St. Charles Parish so that the airport’s east-west runway could be extended into the unpopulated Labranche wetlands. Nationwide, other airports began buying out developments that had crept closer to runways in the preceding decades of mass suburbanization.

Buried deep within the crash investigation report was news of a broken wind-shear detector on the western edge of the east-west runway (the runway where Flight 759 took off); hunters had damaged it with gunfire shortly after it was installed. It was fixed, but hunters shot it out again. “They gave up fixing it,” said Brad Dunbar, a spokesman for the NTSB. Ray P. Sick, a safety officer for the Professional Air Traffic Controller Organization at New Orleans International Airport, reported it in unsatisfactory condition to the Federal Aviation Administration on October 29, 1980; it was out of service for approximately one year and eight months prior to the crash.

Pan American Airlines and the federal government, facing lawsuits in excess of $3 billion, accepted blame for the jet crash in a hearing on May 13, 1983, in New Orleans and offered victims’ families an undisclosed settlement. Wendell Gautier, a lawyer representing several of the victims’ families, called the move “astounding.”

A memorial to the victims of Flight 759 was constructed in a garden at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church in Kenner, one mile from the crash site, where tiles bearing the names of all 146 victims are embedded into a low circular wall.

Once the world’s largest international air carriers, Pan American World Airways — founded in 1927 — ceased operations in 1991 after declaring bankruptcy.

In 2012 Royd Anderson, a filmmaker and high school history teacher from Destrehan, Louisiana, produced a documentary titled Pan Am Flight 759.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Harris, Don. Pan Am: A History of An Airline That Defined An Age. New York: Golgotha Press, 2011.

Sturkey, Marion F. MAYDAY: Accident Reports and Voice Transcripts from Airline Crash Investigations. Plum Branch, SC: Heritage Press, International, 2005.

EXTERNAL LINKS:

NOLA.com, Pan Am Flight 759 crash remembered in memorial, documentary 30 years later: http://www.nola.com/traffic/index.ssf/2012/07/pan_am_flight_759_crash_rememb.html

National Transportation Safety Board Report on Pan Am Flight 759: http://www.ntsb.gov/doclib/recletters/1983/a83_13_26.pdf

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane