Editor’s note: Southern Glossary is a web-based magazine experimenting with different approaches to arts coverage. With a blend of feature writing and blogging, Southern Glossary hopes to provide wide-ranging communication among artists, performers, and art-lovers across the region.

In the City that Care Forgot, sometimes it feels like you have all the time in the world — but sooner or later, exhibits close and the final curtain falls. Southern Glossary and NolaVie are partnering to provide an alternative to the standard arts review. Our monthly Last Call column will give readers fair warning and convincing reasons to catch an event before it’s lights out.

Occupy New Orleans! Voices from the Civil War is an exhibit at the Historic New Orleans Collection that uses art, artifacts, and documents to provide a survey of life in this city during its occupation by Union troops, from 1862-1865. The show comes off the walls March 9th, so whether you try to squeeze it in before the krewes roll down St. Charles or plan to see it after Ash Wednesday, there’s only a brief amount of time left to pass through the threshold off of busy Royal Street and into the pensive rooms of THNOC.

While Occupy New Orleans is heavy on reading material and period illustrations, here are three unique works of art in the exhibit that activate the imagination; you need to make the trip before they head back into the archives.

Farragut’s Fleet Passing the Forts below New Orleans. Oil on canvas. Mauritz Frederik De Haas, painter.

Farragut’s Fleet Passing the Forts below New Orleans, an epic oil painting by Mauritz Frederik De Haas, captures the Union fleet of David Farragut in a firefight with two forts situated on either side of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish as well as Confederate gunboats. De Haas was not yet 30 years old when he was hired by Farragut to chronicle the exploits of his Civil War command. Here he captures the eerie firelight and dense cannon smoke of the pre-dawn battle, and yet, the sky is still full of atmospheric blues. With the perspective centered almost evenly with the horizon, the large scale painting gives the effect of being on the water and watching the battle from a barely safe distance.

The painting hangs in a room dedicated to the tense months before the occupation, when the city was full of trepidation about an attack, and standing in front of its massive scope, you can feel the largeness of the moment when the Union broke through on its way toward one of the most important economic centers of the Confederacy.

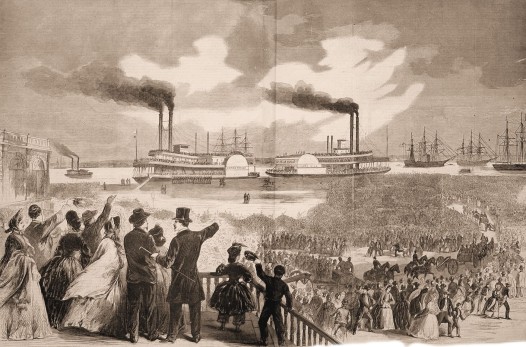

Scene on the Levee at New Orleans on the Departure of the Paroled Rebel Prisoners, February 20, 1863 from Harper’s Weekly. Print. John R. Hamilton, illustrator.

A print of a Harper’s Weekly double-page spread with the caption “The Scene on the Levee at New Orleans on the Departure of the Paroled Rebel Prisoners” depicts a day almost a year into the occupation of the city. Here, steamships depart the port carrying Confederate POWs bound upriver for a prisoner exchange. Thousands of New Orleanians swarmed the levees and wharves to cheer the soon-to-be-freed Rebel soldiers and gather in a rare display of solidarity.

Then, as now, this native crowd had a high proportion of spirited women in it. When Union soldiers were ordered to disperse the celebrating mob, these women waved their handkerchiefs and offered some of the colorful insults they were infamous for. It was a rare day of spectacle and energy in a time when anyone’s house was subject to potential search and seizure, also a period when commerce was drastically depressed.

One item that left a deep impression on me is a small Confederate flag handmade from silk and cotton, the stars made from cross-stitched threads. It is inscribed in French, “This confederate flag was present at the birth of Anatole, Friday, January 8, 1864. He was born during the war.”

Overt support for the Confederacy was outlawed in the city during the occupation, but small, personal emblems of support took many forms, from pins to purses. This fabric memento shows how the passion many felt for the Confederacy went beyond politics and shaded into personal, family concerns as well. It’s also a small reminder that we have the luxury of looking back at the Civil War bookended by its familiar, formal dates. For those living with it as a constant influence on their lives, there was no certainty about when and how it would end or even whether the city would be free to revel on unimpeded again.

Occupy New Orleans! runs through Sunday, March 9 at the Historic New Orleans Collection, 533 Royal Street. You haven’t been yet, so go. More information here.

Ryan Sparks is the editor of Southern Glossary. He lives Uptown but writes all over the city.

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane